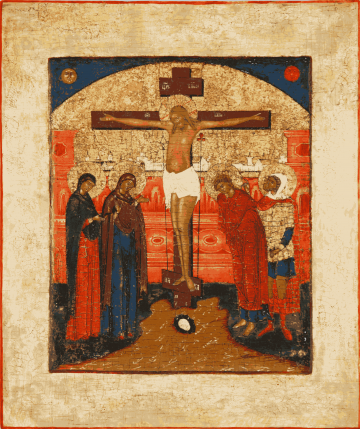

The Crucifixion

(Russia; approximately 1800)

Russia; around 1800; 31.6 x 26.6 cm

Feast: Good Friday

Iconography

The cross did not appear on icons over the first three centuries. The reasons lay in the issue of the cross, which was an instrument of executions, as well as the negative attitude of the Church of the first centuries towards images. This problem could also be related to the lack of templates with the topic. The first beginnings of the depiction of the cross in the Church can be found only after the Edict of Milan (313). One of the oldest depictions of the Crucifixion is an ivory relief dating from around 420-430, which is currently housed in the British Museum in London. It is a depiction of Christ, shrouded in a lumbar apron (perizone), nailed with four nails, without a beard, with eyes wide open and a nimbus around his head. Another image of the Crucifixion is a relief on the gate of the Church of St. Sabina in Rome from 432. Here Christ is depicted with a beard, and the gesture of his hands, which are clasped upwards, is a gesture of prayer.

There has been an evident tendency to abandon the realistic concept since the end of the sixth century. This fact is confirmed by a miniature from the Syrian gospel book from 586 in the Rabbul Code. There are new motifs in this composition, e.g. Christ, who has his head tilted slightly to the left, does not have a hip apron, but a purple sleeveless tunic, the so-called kolobion (κολόβιον). The Byzantine Middle Ages bring a significant change, however, first, since the ninth century, Christ was depicted with his eyes closed and with a hip apron instead of a tunic. Later, in the eleventh century, Byzantine art depicts the dead Christ with a bent body, closed eyes, and his head tilted to the right. Unlike the Western way of depiction, Christ has his feet nailed with two nails, not one. Motifs known since the sixth century, such as a rock on Golgotha with a cave or Adam's skull, are also returning. In the thirteenth century, the background of the Crucifixion was depicted as a high wall, often decorated with cornices and battlements, symbolizing the walls of Jerusalem. In the western environment, a crown of thorns began to appear on the head of Christ from the middle of the thirteenth century, which – under this influence – has since the seventeenth century also appeared in the environment of the East. The legs are nailed with one nail. The rock on Golgotha has a cave and Adam's skull is absent. The depiction of the Mother of God also shows the influence of Western art, which is evident in the position of her hands that are clasped and piously placed in her lap. In canonical depictions, the Mother of God points to the cross with her right hand and supports her face with her left one, which was a gesture expressing sadness already in ancient times. Another element influenced by the West is the scarf on the head of the Mother of God, which replaces the maforion (μαφόριον) typical for the depiction of the Mother of God in older patterns. The background in the composition of the Crucifixion is also influenced by Western art. The walls of Jerusalem were replaced by a realistic depiction of nature with hills, bluish skies and cumulus clouds.

Description of the icon

The centre of the scene and the whole composition is the cross, which in addition to the vertical and horizontal arm also has a lower arm, a so-called footstool, a kind of pedestal on which the feet of Christ are nailed. In many icons, this arm is depicted in an oblique position, which is a symbolic expression of the fate of the two thieves crucified to the right and left of Christ, as confirmed by the words of the Gospel: “Then one of the criminals who were hanged blasphemed Him, saying, “If You are the Christ, save Yourself and us.” But the other, answering, rebuked him, saying, “Do you not even fear God, seeing you are under the same condemnation? And we indeed justly, for we receive the due reward of our deeds; but this Man has done nothing wrong.” Then he said to Jesus, “Lord, remember me when You come into Your kingdom.” And Jesus said to him, “Assuredly, I say to you, today you will be with Me in Paradise.” (Luke 23:39-43)

The Saviour on the cross is not an ordinary dead Christ, writes Paul Evdokimov, but is the Lord, Kyrios (Κύριος), the Ruler over his own death and the Originator of life. Suffering has not changed Him in any way and He remains on the cross as the Word, eternal life, submitting to death but winning over it. This is why the icons do not show, in contrast to the Western realistic way of depiction, the body of Jesus with signs of suffering. The iconographer, as Tomáš Špidlík writes, depicts Christ so that the one who sees him can begin to contemplate the Son of God in Him, albeit crucified, and not the carpenter from Nazareth. If the icon was realistic, the situation from Golgotha would be repeated – when passers-by saw the crucified Jesus they would insult him, as the Gospel states: “Aha! You who destroy the temple and build it in three days, save Yourself, and come down from the cross!” ... “He saved others; Himself He cannot save. Let the Christ, the King of Israel, descend now from the cross, that we may see and believe.” (Mark 15:29-32)

The body of Christ is bent in the shape of the letter S, as if in motion, with his hands turned upwards, while it seems to rise to the heavens. His face also reflects heavenly peace. All traces of suffering disappear in this harmony. The body of Christ on the cross is slightly bent, his nailed arms outstretched and as if raised in prayer, as though he wanted to embrace every human being. His head is tilted to the left, looking at his mother, the holy Mother of God, standing under the cross. His body shows no signs of beatings, floggings and falls from the way to Golgotha, it is instead a body that already emits the light of resurrection. This is also clarified by Tomáš Špidlík: “According to the iconographer, there is no need to depict the crucifixion as it happened. There would not, however, be a problem to depict the scene realistically, but in such a way that those who see it can cry out together with the centurion: ‘This man was indeed the Son of God’” (cf. Mark 15:39).

No art form is able to express the reality of the Son of God, the Saviour, especially when it is shrouded in suffering and death, and thus, as Egon Sendler writes, only the word remains that can say that He is God. It is the name which appeared to Moses in the burning bush and which is an integral attribute in the depiction of the iconography of Christ, inscribed in Greek in his nimbus: “I am who I am.” Another inscription on the icon is the name of Jesus Christ, on both sides of the nimbus, written in Greek, abbreviated IC XC (Ἰησοῦς Χρίστος). The name Jesus comes from the Greek name Iésous (Ἰησοῦς). Iésous is mentioned in the Greek Septuagint as a transcription of the Hebrew name Yehoshua, or Yeshua for short (Yahweh is salvation, Saviour). This name was extremely widespread at that time in the area where Jesus lived.

Christ (Χρίστος) is not a name, but a title, which in translation means Anointed. This word is a translation of the Hebrew word Messiah, which means anointed by Yahweh or anointed by God. There is usually a title, the inscription that Pilate affixed, stating the reason for Christ's conviction above Christ’s head, “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews; ... written in Hebrew, Latin and Greek” (cf. John 19: 19-20). In Greek - Ἰησοῦς ὁ Ναζωραῖος ὁ βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων, abbreviated: INBI; in the Slavic ecclesiastic language - Иисус Назорей, Царь Иудейский, abbreviated: ІНЦІ and only for comparison also the Latin version of the text - Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudeorum, abbreviated: INRI. This is also accompanied on Greek icons by the text Ο Βασιλεύς της Δόξης, in Slavic ecclesiastic Царь Славы – King of Glory, or by the testimony of the centurion: Υιός Του Θεού – Son of God. The Greek νῑ́κη – ‘winning’ is at the bottom of the cross. These inscriptions provide the Crucifixion with its true dimension.

The Mother, the Blessed Virgin, always appears to the right of Christ, whose head is slightly inclined towards her. She points to the cross with her right hand, and the expressiveness of this gesture is emphasized by the immobility of the left hand, the fingers of which seem to want to relieve the chest of its unbearable grief. A tragic voice of silence is heard in the position of the fingers. The Blessed Virgin is frozen in her grief, with a sword piercing her soul. Her traditional dark dress contrasts with the pale body of her Son. It is not completely clear who the other woman is. She represents, according to the Evangelists, Mary Magdalene or Mary, the mother of the Apostles James and Joses, and Salome, the mother of the sons of Zebedee, James and John, or “and many other women who came up with Him to Jerusalem.” (Mark 15:41) They stayed with the mother of Jesus, supported and consoled her.

The Apostle St. John, the beloved disciple of Christ, is the only apostle who remained under the cross. He is usually depicted to the left of Christ, most often in a red or dark red to burgundy top garment, the underwear is light, usually blue. He has a slightly bowed head and clasped hands, which, as Tomáš Špidlík writes, expresses the contemplative attitude of a person who, from what he sees, accepts a thought into his heart. It is the attitude of a disciple whose head rested on Christ’s chest on the eve of Christ's death and who now contemplates him in mysterious agony. He is immersed in his core, sensing the mystery of Christ's suffering.

There is the centurion to the left of Christ, behind the apostle John. An important detail in the figure of the centurion is the gesture of his right hand, in which there is no spear piercing the side of Christ, as was the case at the beginnings of the depictions of this scene. He instead points to Christ with his hand and testifies in front of the soldiers present and others: “This man was indeed the Son of God” (cf. Mark 15:39). In some depictions, the head of the centurion is wrapped in a kind of white cloth. This iconographic detail is not accidental. The white colour, as stated by Tomáš Špidlík, represents a spiritual reality in iconography. It points out that he has a spiritual idea, i.e. in the middle of the Golgotha scene, looking at the crucified Christ, he can see the spiritual meaning that takes place before his eyes and can internally recognize the divine dimension from what he sees with his outer eyes.

Golgotha, the place of the skull, the vertical arm of the cross attached in the earth is the place of descent and exaltation of God's Word, the link between heaven and earth, so that the heavenly may unite with those who dwell on earth and in the underworld. The lower part of the cross is therefore set in the ground, in a rock with a dark cave, where Adam's skull is located. According to the Apocrypha, Adam was to be buried on Golgotha as a prediction of the sacrifice of the cross. We therefore always find a cross erected on a rock above a cave, in which lies Adam's skull, marked with the letters ΓΑ - Adam's head. It is a symbolism inspired by St. Paul's letter to the Romans: “Therefore, as through one man’s offense judgment came to all men, resulting in condemnation, even so through one Man’s righteous act the free gift came to all men, resulting in justification of life.” (Romans 5:18) This symbolism is highlighted by blood on some icons, trickling from the wounds of Christ, which washes Adam’s skull. This symbolic detail indicates the head of the first Adam, and in him all mankind is washed with the blood of Christ as a sign of forgiveness. This is also confirmed by the symbolic letters on the cross under the footstool at Christ's feet – M Л Р Б – Место Лобное Рай Бысть – the skull place became paradise. The letters Д Р - Дерево Pайское – the tree of paradise under Adam’s skull can also be seen in some icons. Adam's skull can be compared to a wheat grain, which, planted into the ground, dies, but a new life grows from it (cf. John 12:24). This is how the wood of life grows from Adam's skull. The Apostle Paul teaches us this: “For since by man came death, by Man also came the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ all shall be made alive.” (1 Corinthians 15:21-22).

The Walls of Jerusalem, the scene of the Crucifixion, are situated with the city walls of Jerusalem in the background, behind the cross. This symbolic element, which is not absent in the iconography of the Crucifixion, is also based on the Holy Scriptures, where the Apostle Paul writes: “We have an altar from which those who serve the tabernacle have no right to eat. For the bodies of those animals, whose blood is brought into the sanctuary by the high priest for sin, are burned outside the camp. Therefore Jesus also, that He might sanctify the people with His own blood, suffered outside the gate. Therefore let us go forth to Him, outside the camp, bearing His reproach. For here we have no continuing city, but we seek the one to come.” (Hebrews 13:10-14) St. John Chrysostom in the homily of the feast asks the question: “Why did he suffer outside the city, on a hill, and not in some covered building? For a simple reason. To cleanse the contaminated air, that is why at a high place, under the sky, to cleanse it through the sacrifice, on the cross of the high Lamb. This cleared the heaven and restored the earth. The blood that flowed from Christ's side washed away any dirt and filth. Why didn’t such a great sacrifice take place in a sanctuary of the Jews? This happened neither by chance, nor without a cause. So that the Jews might not appropriate Him, only for them was this sacrifice made. That is why this sacrifice of Christ on the cross took place outside the walls, so that we could see that Christ made this sacrifice for the whole world and thus redeemed all mankind.” The Crucifixion took place outside the city where the chosen nation of the Old Testament lived. It is a symbol of Christ's redemption for all the nations of the world. One can return to life with God through Christ’s death. Only through the Cross can one reach the Holy City – the Glorified Jerusalem.

The sun and the moon are at the top of the icon: “there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became like blood.” (Revelation 6:12) The sun and the moon represent the New Testament and the Old Testament Church, but also the physical and the spiritual world.